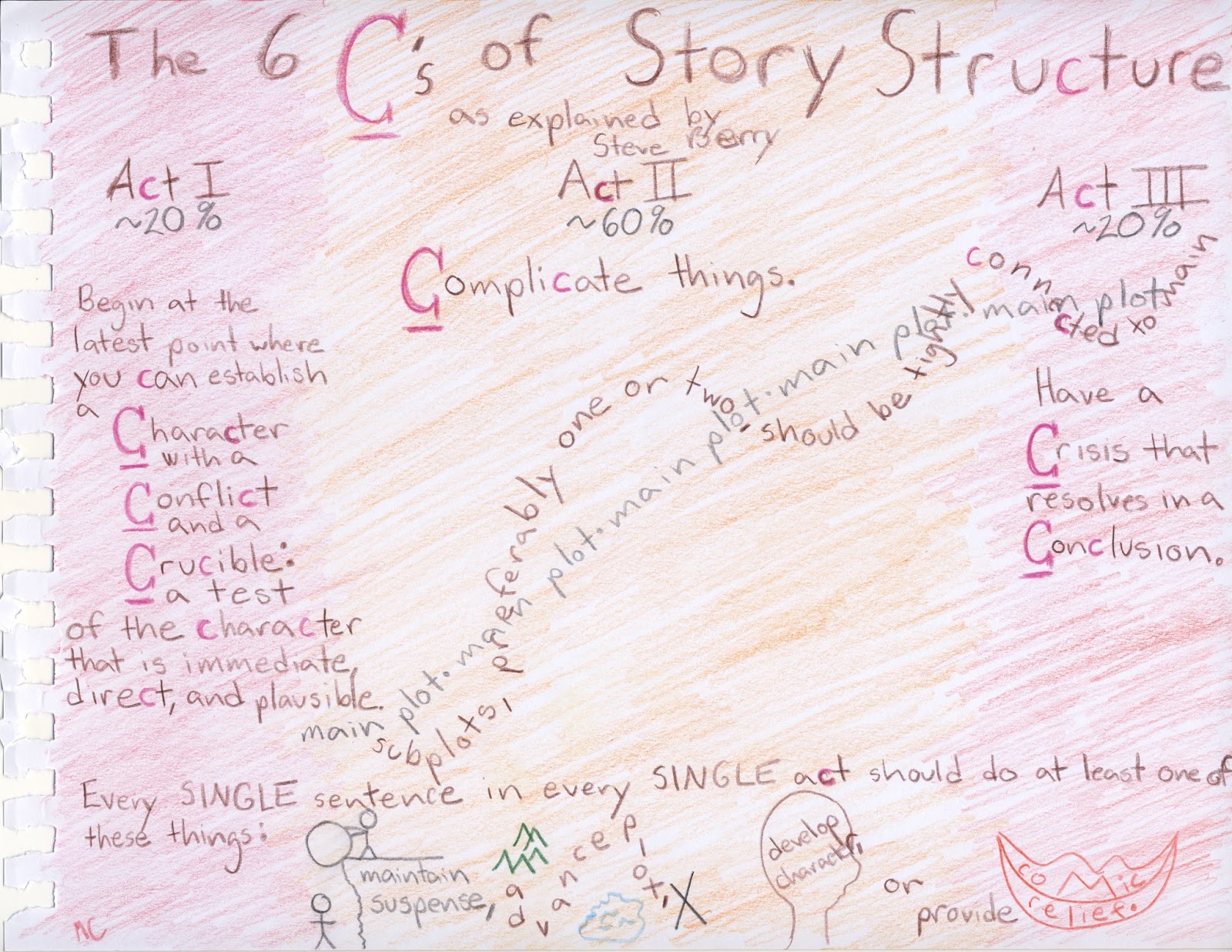

Recently, I attended ThrillerFest in New York. It was a fabulous experience. The experience of pitching to agents is a blog post all on its own. But when I was asked to write about my trip, I wanted to share the most practical advice I received. That advice came from a presentation Steve Berry gave entitled "The 6 C's of Story Structure." It was the most succinct and clear description I've heard of story structure anywhere. Like something worthy of being animated by RSA Animate. I don't quite have their talent, but I did put together a little graphic that illustrates everything I'm about to say.

Any story (no matter the length) can roughly be divided into three acts. In the first act, you need to establish a CHARACTER with a CONFLICT and a CRUCIBLE. The crucible should be a test of the character that is immediate, direct and plausible. Let's take these elements one by one.

Immediate: the reader should feel the danger, not just intellectually understand it. Your heroine is at risk of losing something precious (career, love, life, magic artifact). If you've established a character the reader cares about, then the risk of losing that precious object will pull the reader in.

Direct: the test of character should be imminent. It shouldn't be like figuring out a tournament bracket, where your heroine will have her character tested if some chain of events happen. It should be clear that something interesting and significant is going to happen.

Plausible: the crucible should feel like it naturally derives from the character's background or where your story is set. For instance, a detective being asked to solve one last murder, even though he's retired. Or a tropical disease specialist being asked to track down the source of a mysterious infection. Notice that if I switched those two characters around, things get a little confusing. Why would a tropical disease specialist be expected to solve a murder? Or a ex-detective be asked to dabble in epidemiology?

And if you really want your crucible to test your character, make sure it's a test of character. The heroine who gladly jumps into danger isn't nearly as interesting as the character who is dragged in against her will. Think of Katniss in Hunger Games. Her desire to protect her sister is in direct conflict with her desire to be a good person. To quote Steve Berry directly, "The best conflict is a conflict of heart."

Keeping the first 3 C's in mind clarifies a question I often find myself asking: where do you start a story? You start at the latest point where you can establish the character, conflict and crucible. Start too far after that, and your readers will feel like something is missing. Start too far before, and your readers will stop reading before they get to the good part.

In the second act, you COMPLICATE things. This should be about sixty percent of your story. Your heroine is fighting, clawing, struggling and you keep pushing their desires just out of their reach. Your subplots should weave in and out of your main plot, contributing to the tension. About halfway through the second act, it's helpful to take a step back and examine the first act, to make sure you've included all the necessary elements.

That tension rises until you reach the third act, where there's a CRISIS that resolves in a CONCLUSION. The third act is about twenty percent of the story. The main plots and sub plots should settled at about the same time. Try to wrap up those plots as close as possible to the end.

And while you're doing all of that, make sure that every single sentence in every single act does at least one of these four things, preferably more: maintain suspense, advance the plot, develop character, or provide comic relief.

Easy, right?

Megan Carney

Website: www.megancarney.com

Blog: openletters.megancarney.com